Does Buddhism Really Work? Buddhism and Psychotherapy

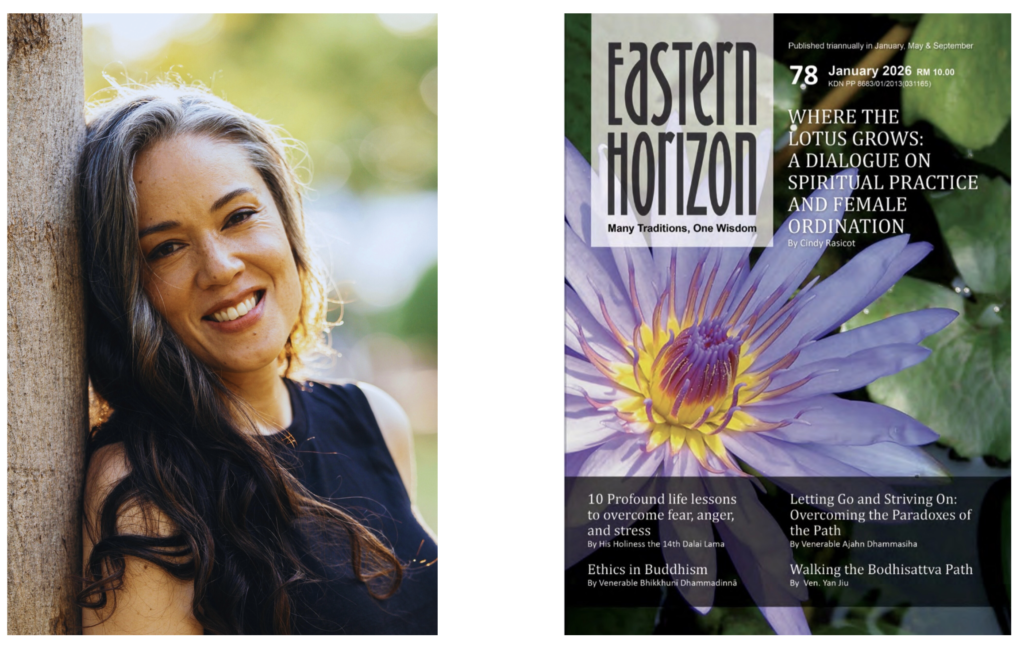

‘Can Zen Make Us Happier? Buddhist Wisdom for Modern Lives and Busy Minds‘ is an interview with Mia Livingston and Benny Liow, Editor of the Young Buddhist Association of Malaysia’s magazine Eastern Horizon (pp. 51-55, January 2026)

Mia Livingston is a doctoral candidate researching somatic psychotherapy and autoethnography at the University of Edinburgh. Featured in TEDx, the Guardian, BBC Radio and as editor to the Buddhist Society in the UK, she has been studying and writing about Zen Buddhism since 2004. Benny Liow was able to interview Mia about her interest in Buddhism, especially Zen, and the relevance of Zen Buddhist teachings for the well-being and happiness of today’s much stressed society.

______

Benny: Can you tell us about how you first became interested in Zen? Was there a particular moment or experience that drew you to the practice?

Mia: In retrospect I was drawn to Zen before I knew what it was. Even as a small child, I felt consumed with a search for answers to suffering and to the meaning of life. But nowhere I looked and no one I asked seemed to know the answers, until finally aged nineteen I came across Philip Kapleau’s classic work The Three Pillars of Zen.

I devoured it, amazed to learn that such an ancient wisdom practice was still alive somewhere in the world today. This was before the internet, so as far as I knew, the only places you could study Zen were monasteries in Japan. I resolved to go there and study as soon as I could. Until then, following the detailed instructions in the book, I tried to sit zazen at home on my own—bunching up some pillows and sitting cross-legged on a mattress for a few minutes at a time.

It was extremely hard of course. Without a teacher I got nowhere. Abiding quietly in my mind felt like entering a storm without a lifeline. I gave up until a few years later, when I had the opportunity to attend Vipassana sessions at university.

It was much easier to sit with others. But my intellectual mind was still much stronger than my ability to sit, so when university ended my practice did too.

Day-to-day life took over for some years until a woman I interviewed during my work warmly recommended S.N. Goenka’s ten-day Vipassana sits. That enabled me to go a little deeper, and yet I knew I was only scratching the surface. I still had so many questions that it seemed nobody could answer.

Finally aged thirty-three, I found Zen in practice. I was struggling in all aspects of life. My relationship, family situation, work and friendships all seemed to be going horribly wrong. There was nothing to hold on to; it felt like I had nothing to live for. With perfect timing, an acquaintance mentioned in passing a Zen retreat not too far away that he’d attended. I was amazed—that was the first that I’d heard of there being Zen retreats in the modern day and in my country. Maybe I wouldn’t have to travel to Japan after all?

I phoned them. They said that they were booked full, but recommended a monastery further north. The monastery said that they were fully booked too, but I must have sounded desperate because they kindly made an exception and let me come for the next introductory weekend.

Finally, I felt that I had found my place. About twenty-five monks were resident there, and many of them were able to answer my questions. I loved the way that they came across: calm and modest, but also light-hearted and compassionate. They had a library and several monks had doctorates, which meant that they taught Buddhism in a way that my overly critical intellectual mind too could engage with.

I returned as often as I could for a week’s sesshin (intensive retreat) at a time. I was a hard nut to crack. Despite all the zazen and studying, I continued to feel full of despair. Meanwhile my situation at home was deteriorating. There seemed to be only one thing for it: I asked if I could stay longer as a resident. These days there are many organized residential programs that you can easily apply to online. Back then and there, unless you wished to be a monk it was unheard of.

They were tentative and reviewed my stay every few months, but I ended up staying for a year. I actually felt from the start that that was the amount of time that I would need for my understanding to gain sufficient traction to be able to continue on my own.

Many have asked me why I didn’t “just” stay and apply to become a monk. They assumed that anyone who could, should and would apply to walk that path. My answer to that question is hard to explain. I wanted to want to. I loved the teachings and the monastic community; while it wasn’t easy, I felt happy and at home there; and no relationship, desire, or job was calling to me from “the world” (as life outside the monastery is often referred to). In one article I joked that “I feel more at home in a whisky bar than an abbey”, although the truth is that I feel equally at home in both. (That said, if I had to choose one, I’d choose the abbey!)

I was driven by an unformed and yet certain feeling of having a vocation “in the world”. As I mentioned before, I felt consumed from an early age with a search for answers to suffering and to the meaning of life. But it was more than that: I felt driven to apply those answers to whichever form that suffering was currently taking among people in general. And in order to do that, I had to be in the midst of it with people who were going through relationships, anxieties, politics and so on.

I felt grief about that choice—it seems common for us humans to feel grief about whichever paths that we don’t take. At the same time, there is gratitude for the richness and joys that come my way.

I ended up studying and qualifying as a psychotherapist. Currently I am a doctoral candidate studying experientially the influence of somatic psychotherapy and Zen Buddhist practice on the healing of complex trauma. I’m also a writer, and aim for my research to be published in book form eventually.

From your own experience, how has Zen practice influenced your sense of well-being or happiness? Are there particular aspects of Zen that have been especially helpful?

When I found myself not knowing what to say in sanzen (private interview), my first Zen teacher would ask me “what feels important right now?” or simply “what’s important?” My therapist asked the same thing, and I learned to always go back to that until it eventually became an inner “place” that I habitually “lived in”, a compass that I navigated by. The question led to what feels like a big, calm and quiet space in my gut, and it’s a perspective that undercuts anxiety and slows time down. (If there was a song for it, it would be Louis Armstrong’s “We have all the time in the world”.) This depth of being results in being less swayed by the caprices and pulls of our constantly changing world.

Contrary to what I thought would happen, slowing down has actually allowed for more activity rather than less. Life became bigger and could hold more. Despite being in my 50s I’m much more active, confident and positively motivated now than I was when young.

There’s also an impulse towards connection that clarified with practice. I used to jump into new friendships and jobs without thinking much about it. The impulse that arises from Zen practice skews more naturally towards service. I ask myself what I can add to a situation if anything. If I can’t add anything then I don’t engage. If I can, then it often happens instinctively. And it goes both ways: I only engage with new friends or work when the connection is nurturing. This may seem obvious, but from a psychotherapeutic perspective there are many unhealthy reasons why people engage. Friendships, work and relationships are healthier now.

As both a psychotherapist and a Zen practitioner, do you see similarities between Zen practice and psychotherapy when it comes to supporting mental health? Where do they align or diverge?

I think they both have the capacity to contribute to the alleviation of suffering, and personally I needed both. You could think of it as Zen forming the bones of practice and psychotherapy the flesh. While Zen eventually (and slowly) woke me up to the direction and purpose of my life, psychotherapy taught me how to walk that path. But there is no clear-cut line between the two; they overlap, and everyone’s needs and experiences vary.

One major difference is that while Zen training took place within a community, ultimately you can only do your own training, and you can only do that within yourself. Even though Zen Buddhists often sit side-by-side, it’s mostly silent and it can feel lonely. Psychotherapy on the other hand is social by nature, because you’re figuring things out together with a group or a person.

After years of sitting zazen and solitude in my life generally, I thought I was very good at being alone and at abiding by the precepts. But it turned out that I had just been repeating the same egotistically defensive narrative over and over again in my mind. I could act in accordance with the Zen community and my narrative might have refined a bit, but it was still there. Only psychotherapeutic inquiry with other people could and would break through that.

An insightful Zen teacher and a good psychotherapist see different things. Some trainees imagine that their Zen teacher sees everything; but even when a Zen teacher is a trained therapist, I don’t know if that’s true. It can be healthy to have multiple mentors, teachers, and sources of support.

Your research focuses on “personal narrative” — how do you see the role of storytelling or self-understanding in Zen practice, which often emphasizes letting go of the self?

Storytelling has likely existed for as long as humans have; it’s a way of sharing, connecting and healing. And in a very real sense, while we are connected, we are also separate individual human beings having separate individual human experiences. What is this strange life that we’re living, and what are we all learning from it? In my experience ignoring our differences is more harmful than acknowledging and maybe even celebrating them. Writing about the particulars of personal experience spreads understanding and empathy. It also taps into the universal, and can be a way of sharing Buddhist practice.

I work with autoethnography, which emphasizes understanding and writing about everything that both the “big” and “small” self is connected to, mutually influenced and sustained by. This includes relationships with humans and non-humans. It’s a kind of storytelling that seeks to clarify the role and place of the self as one of an infinite number of beings in an equal (if not always equitable) universe.

For sure there are forms of personal narrative which are unhelpful. You could do it for attention-seeking, or you might cast yourself perpetually in the role of a victim. Alternatively, through for example somatic psychotherapy, you could share deeply and honestly about painful experiences in a way which helps to connect us and process your karma for yourself and others. It would be a shame to miss out on the healing and connecting power of storytelling for fear of the former. After some practice you can trust yourself to feel the difference, and if you take refuge in the precepts, you can’t go far wrong.

Zen is often associated with monastic life. How do you see its relevance for laypeople — especially those balancing work, family, and modern responsibilities?

Many monastic friends have agreed with me that we do not see a significant difference on either a deeper or day-to-day level between monastic and lay life. Monks have numerous responsibilities that they balance too—monasticism can even be more hectic than lay life. Both monks and lay people take vows, practice zazen, study the Dharma, do their best to follow the precepts, do the dishes and laundry, cook, clean, work, exercise, relax, socialize, and care for our family or community.

So what then is the real difference between us? As I understand it, monastics are the formal lineage holders and teachers of the Dharma. It is their work, their vocation, and there are daily rules and rituals in place that support them to carry out those responsibilities.

As a lay person, on the other hand, I am not formally a Buddhist teacher. I’m Buddhist and I teach—but that’s not the same thing. I don’t take disciples or conduct ceremonies. I have taken the lay precepts and I strive for my work to be helpful and compassionate; but all my actions and choices are not held to anywhere near as close scrutiny as a monastic’s.

You could argue therefore that the teachings are more important to lay people than to monastics, because they are not built into our lives in the same way. Zen teachings have given me a solid sense of guidance and direction in all the areas that you mention. In other words, Zen couldn’t be more relevant to my lay life. In terms of the heart of the matter—compassion, freedom from suffering, and our commitment to do the best that we can—the relevance of and our need for Zen practice is the same.

Could you share a few ways you personally integrate Zen into daily life? Are there small practices or shifts in perspective that lay practitioners might find useful or accessible?

Moving your body gently can shift your mindset to a more open and nurturing one. I love doing kinhin (slow walking meditation) whenever I feel the need to slow down or get clarity. It’s no substitute for seated meditation; but it’s quick and easy to just get up from your work or chore for a minute, put one foot in front of the other, and notice every small part of the sole of the foot as it slowly, gradually comes to rest on the floor.

Another way that I integrate Zen into daily life is during challenging conversations, when possible. If I feel a conversation starting to turn into an argument or upset, I drop my attention down into my lower abdomen in the same way that I do in zazen, and ask myself questions from that place. Do I feel afraid? Worried? Protective? Why? Often it’s possible to begin to get to the bottom of something, which in turn can change and deepen the course of a conversation.

Have there been moments where Zen practice felt difficult or even conflicted with your emotional needs or relationships? How did you work through those tensions?

As a person with neurodivergence and a history of complex trauma, the harsh and collectivist training model traditionally used in Zen Buddhism was not always healthy for me. Any needs or sensitivities that differed from the norm might be judged by some well-meaning teachers to be self-indulgent, deluded, or “not training hard enough”. But there is room for gentleness and understanding without compromising rigor and veracity. It isn’t an easy balance to strike—but many teachers have done a great job of it, and the tradition is progressing in the direction of understanding trauma. Personally too, following autoimmune health issues I’ve had to learn to be much kinder to myself mentally and physically.

Related to that, I had to relearn assertiveness and healthy boundaries. Zen training can be confusing: students learn a spiritual practice of deep acceptance, but there will be people who take advantage of them because of that. They are taught to be like the old man in the parable of the lost horse where he remains equanimous regardless of gains, losses and others’ judgments. Righteous and constructive anger—and arguably even most forms of emotional expression—are not encouraged. I was praised as a trainee when I twisted my body and exhibited the traumatic “freeze” response. Following this logic to take an extreme example, what happens in cases of assault or unfair dismissal from work? I had to “un-freeze”, regain access to my full register of emotional expression, and learn to defend myself—even though in Zen understanding there is not ultimately a “self” to defend.

Has your understanding of “well-being” or “happiness” changed as your Zen practice deepened? If so, how would you describe that shift?

One thing that I wasn’t expecting is how sensitive, aware and fully engaged with my environment that I would feel after years of practice. For some reason I had interpreted “inner peace” to mean a sort of dissociation from the world; but the reality is the opposite of that.

I also thought that joy and the feeling of nurturing would come from some kind of holy “other” spiritual place. But it comes from that very grounded connection with your environment and all the things and people that you encounter in it.

_____

© Mia Livingston 2026. All rights reserved. Welcome to quote and link to this article, but do not edit or reproduce it in any form without permission.

.Where’s home?

As a “Third Culture Kid” one of the hardest — and saddest — questions to answer, is also one of the most common: “Where are you from?” I interrogate the meaning of ‘home’ in an essay for the Journal of the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives.

.Talking about love in the Telegraph

My husband and I are featured on the cover of the Sunday Telegraph’s lifestyle today, “Against my will, choice and better judgment I found myself helplessly in love: four couples explain how fundamental differences in personality, lifestyle or upbringing have not stood in the way of happiness.” (Paywall alert. Mom, is that you? I’m sending you copies!)

If you’re new to my site, welcome! I’ve been writing here at least once every three years, but things have been going so well that I’m ramping up to possibly double or even triple that. Feel free to subject yourself to my TEDx about love, mailing list and blog posts (on the right if you’re on a computer, or below if you’re on a phone). There’s also my bio, twitter, and contact info – I’d love to hear from you – and my most recent post about a Zen monk who quotes Ruby Wax.

A note about the mailing list: along with my website it’s a bit rickety at the moment; to be on the safe side, simply send an email to ZenInPractice@gmail.com with “Subscribe” in the subject line.

.Make A Wish Like A Zen Monk

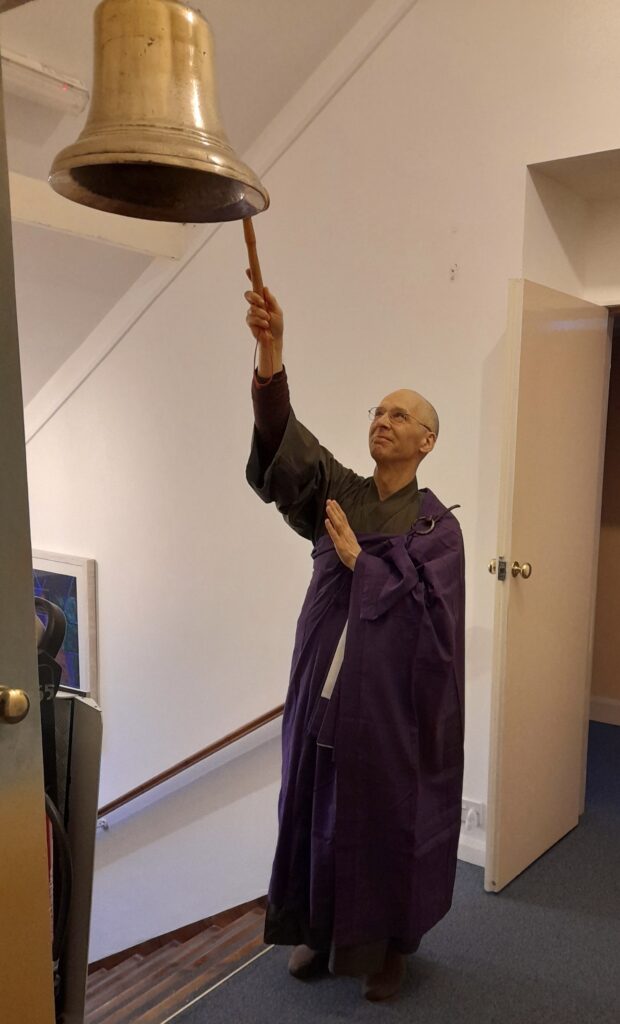

Last New Year’s Eve, I was moved by a talk that a Zen monk gave about how to make a wish. It struck me as a skill that everyone could benefit from, and not just at New Year’s, so he kindly let me publish a short version of it here. (You can also listen to the full talk here.)

“At the abbey we celebrate the New Year by gathering at the altar, and revolving the Scripture of Great Wisdom (also known as the Heart Sutra). The celebrant opens the scripture like a concertina and revolves it around, to symbolise what we think of as the living and moving qualities of the truth. At the end of the ceremony, each participant in turn rings the big monastery bell. In that moment they silently make a wish — or a vow — for the coming year.

You could do your own version of this at home: maybe do some meditation in the evening, offer incense or strike a small bell if you have one, and make your own wish or vow.

What I’d like to focus on in this talk is the attitude of mind that we have when doing that. New Year’s resolutions can be tricky: while it’s natural to have an aspiration to improve yourself or your life, the goal-setting in itself can become just another distraction or avoidance. In her recent book ‘A Mindfulness Guide For Survival’, well-known comedian Ruby Wax writes well about our reactions to covid, and of typical forms of avoidance:

“We were suddenly forced to confront the harsh truths of difficult emotions, uncertainty, loneliness, change, dissatisfaction and death… […] Of course, deep down, we know everything changes and everything is uncertain. We’re alone, we die, blah blah blah. But who wants to go there, when there’s so much on Netflix to watch? […] We’ve been too busy to notice disturbing realities because we were all on a tight schedule of ‘must do’ things—most of which were things that didn’t ever need to be done.”

We can be trapped by so-called time-saving devices like the smartphone but are at its beck and call, waiting for it to ping so that we can ping back. I have a smartphone and occasionally measure how many steps I take in a week to keep myself fit, so I can appreciate how anything like that can become a bit addictive.

What all this is pointing out, for me, is that we need to clarify the wish we make in a way that isn’t just another form of measurement or another ‘must do’ thing. We need to get underneath the whole concept of ‘things we must do’. What are the real ‘must do’ things? If we were going to ask ourselves just a single question to clarify what our wish is, it would be: What is the most important thing?

Self-help techniques, mindfulness techniques, and ways of measuring progress, can be very helpful; they can give stability when you’re dealing with for example depression, or finding ways of coping with daily life. I’m not knocking those.

Sometimes, however, they can also encourage an unhelpful kind of thinking, where we see ourselves as objects—as if we’re watching ourselves in a movie, to see how well we’re performing. The next thing we know, we’re measuring our progress in terms of how much meditation we do. Then we install an app to measure meditation—and our wish has become just another ‘must do’ thing.

A real wish is much deeper than that. Don’t let yourself avoid the question, What is this self? What is this being, that wants to achieve?

If you achieved all your measurable goals, would you be happy? Or would there still be a sense of lack, if you’re not careful? If you achieve 6,000 steps a day for example, maybe you’ll be fitter. But the ‘being’ that’s on a fitness app in terms of heart rate, number of steps, and hours of sleep, must not be confused with what you really are.

Not everything can be measured in terms of success and failure, because no matter what we achieve there’d still be a ‘me’ that seems to be the centre of existence; that seeks to control the world in order to find the most comfortable place. It’s an instinct. We’re so used to controlling things; to thinking about what we want to achieve and how to achieve it. We want to know what is happening, so that we can control the results. This works well—to a point. As soon as for example our health fails though, it’s clear that we’re not in control. Some things cannot be known in the way that we’d like.

We can learn to respect that; to accept and acknowledge that there’s a horizon over which we cannot see. That allows us to remain in awe of life and death, and to have a more realistic sense of our limits. It’s ok for some things to remain as question marks, without our seeking reassurance.

To bring this back to making a wish: maybe just for the moment we need to cease from measuring completely, and just trust the intention and its sincerity. What is the most important thing?

Zen Master Dōgen wrote that if you “simply let go of body and mind and let body and mind fall away naturally”, you will “effortlessly gain freedom from suffering”. I sometimes wonder about the ‘effortlessly’, and suspect that it actually takes a particular kind of effort just to remind ourselves not to let our vanity and ego get in the way. There’s a difference between a practice based on protecting and enhancing the ‘me’, and a practice that sees through the illusion that we are the centre of existence.

In our practice, there’s bowing. The founder of the monastery was taught that when bowing stops, Buddhism stops. Interestingly, the more senior you become in the monastery, the more bows you have to do! Three before meditation, and six before and after morning service. It’s all to remind you that while you might be ‘in the centre’ at the moment, there’s more to it. It’s an acknowledgment that “I don’t know everything, and never will. I don’t even know what will happen today, but I will do my best. However important I may feel myself to be, there is always much more…”

This doesn’t mean that there’s a higher being, necessarily; it’s simply a sense that our relationship with existence is deeper than we can fathom. My body, life, mind, and time are not really mine: they are ‘owned’ by the world. We have some control, but what could any of us do without the support of everything around us? Our lives are constantly connected to that of others, and to existence itself.

Bearing these things in mind, the personal wish or vow that we may want to make has to come from within. Leaving aside what we are told that we must do or must have, just by looking for it we are doing something positive. What is it within ourselves that we can trust?

We can sit through many things. Just as the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree before his enlightenment, we can allow all the pulls and pushes, the pressures, all the things we feel we must do, to settle so that we can clarify out what is truly important. Help is available, whatever you may call it: intuition, Buddha nature, a still small voice.

Don’t worry if it seems trivial. It could be as simple as being kinder to someone you know. Just doing one thing with a sincere mind is always enough. We don’t need to vow to save the world. The moment of respect, or an act of offering—even bowing once, or making a sincere wish—can transform the mind, and even embrace the whole universe.

The physical act helps. It’s in the doing that our connection is realised, and it works because of that connection. Our efforts may not save all refugees or stop global warming; but there is something inherently good in making the offering, that warms the heart and connects all beings.

Clarifying your wish is ongoing. It’s fine for it to remain undefined, as long as you keep reaching. The searching and the goal are not separate; the asking and the answer are not separate. They come together. So strike a bell, or do some bows, or light a stick of incense. Make your wish, and trust your heart in doing so.”

Edited from a talk by Rev. Berwyn Watson.

(Find out more about Throssel Hole Buddhist Abbey on Facebook or Youtube.)

.Online Zen retreats during Covid

I wrote a thing about online Zen retreats during Covid, on the front page of the inaugural issue of mental health magazine The Breakdown. Hope you enjoy it, feel free to read and share.

https://the-breakdown.co.uk/how-online-zen-retreats-are-helping-me-get-through-lockdown/

https://twitter.com/TBreakdownMag/status/1334455093689724929?s=20

.From Astronauts To Psychotherapy

I’m happy to report that my TEDx talk on love has now reached more than 2,000 views! (Update in 2020: 400K+.) Click here if you prefer to read a transcript. If you’re up for an easy challenge, play spot-the-resemblance in this talk by former NASA astronaut Ron Garan which he made on the same night. I studied at a monastery, he studied in a spaceship: we started from opposite perspectives, but arrived at the same conclusion.

“The Key to any and all success is We” — Col. Ron Garan

Apologies to blog readers — this year I’m experimenting with writing more offline than online. Projects in the pipeline are a book on love, and an essay for an anthology on Buddhism and psychotherapy. I even wrote with actual ink on actual paper a few weeks ago. With my hand. Having said that, the best way to stay updated is to subscribe via the website and follow me on facebook.

I’m also training in counselling and Buddhist psychology. I can’t wait to work as both a counsellor and a writer. To my mind, the two professions go together perfectly.

If you’re new to this site, I hope you’ll feel welcome. Feel free to have a browse through my articles and subscribe to updates above.

.Q&A: Where should I study Buddhism?

“Hi, I was thinking about a long term stay in a monastery, but I have absolutely no idea which ones are most suitable for me. I know that there are several kinds of ways in which the Monks live and guide you, but apart from what they are called (Theravada, Mahayana, Tibetan), I know nothing. Would you please give me a brief information about the differences, pros and cons of all three? I would be really grateful. And maybe point out several monasteries that are the most friendly and open…? Thanks a lot.” – Jeremi

Hi Jeremi, thanks for your question! This is a good comprehensive article about it. [Link may be broken–google it!]

The thing that worked best for me, was researching which monasteries were accessible to me (with the help of google and the buddhanet directory), and visiting the ones that appealed. You can quickly get a sense of what a place is like, when visiting. You’ll also meet people who are happy to tell you about other places that they’ve been to. This is a post of mine on what to do when you get there.

Aside from the points mentioned in Alan Peto’s article that I linked to above, pros and cons depend on what works best with your personality and needs; and the differences can be so subtle that you won’t know until you’ve stayed somewhere for a while. Some places are friendlier to men than to women, for instance, and everyone’s definition of ‘friendly’ differs; so I couldn’t possibly tell you objectively which was the friendliest. Having said that, if ‘friendly’ and ‘open’ is what you’re looking for, then Tibetans are the first to come to mind!

While I loved all the monasteries I visited, I chose an English Zen one in the end because the way they were, and the way they did things, ‘clicked’ more with my personality than the others had. Because of that, their teachings were the easiest for me to understand. I think much of it was down to culture rather than to Buddhism, since I relate relatively easily to English and Japanese culture. Many of my friends chose Theravada or Tibetan schools instead, and knowing them, that makes total sense. Yet others chose to study in a more relaxed place like the Sharpham Trust in the UK, even if it isn’t explicitly Buddhist.

At the end of the day, I think the important thing is not technical differences, but that you find yourself a good place to study, that you like, run by a trustworthy and established lineage of teachers. Good luck!

.What is Love? TEDx

I had great fun making this TEDx talk, I hope you’ll enjoy it.

Transcript: “My parents met against all the odds. My father was born in Sweden, my mother in the Philippines. They lived 6,000 miles apart. They were born during WW2. The way they met was that their schools arranged an English exchange: for them to learn English through letter writing. They loved sharing their curiosity about the world and about different cultures; they exchanged photos that they’d made themselves. After three or four years, they started to fall in love without even having met. As soon as my mother finally made it to Denmark, Dad hot-footed it over after about 5 years of letter-writing, immediately proposed the same day, and my parents have now been happily married for almost 50 years.

My parents, who met against all the odds, celebrating their anniversary where they honeymooned in Paris nearly 50 years ago.

So I thought love is this easy ideal of a man and a woman meeting, having three healthy children, and everything works out wonderfully. They made it look so easy.

I spent the next 20 years of my life following this ideal and trying to match it with what I’d seen when I grew up.

When I was 17 I put out a penpal advert, because I thought I’m going to meet somebody in exactly the same way as my parents, because that’s obviously the way it works. Unfortunately all I got in return for the advert was pictures of penises and an invite to Florida from a middle-aged man that I’d never been in touch with in my life.

Eventually I did meet a tall dark handsome stranger, who was a very kind man; but unfortunately we weren’t matched. The thing is, I didn’t care about that; because I had this ideal, and I was going to make it happen no matter what. Sadly after seven years we had to split up, because we finally had to acknowledge that we weren’t getting on.

At the same time, I was working with developing countries and with charities. I’d also grown up in a lot of poor countries. My heart was breaking in more ways than one. I no longer had faith that the world was a good place to be. I was close to 9/11 when that happened; I was very close to the London bombings when they happened four years later.

At the same time, two people who were the closest to me said that they hated each other and never wanted to see each other again. My sister was in a near-fatal accident, and my heart just broke. I thought, “I don’t want to be in a world like this.” I just thought, there isn’t any point. It’s a very dangerous place to be, because if you’re depressed at the same time that you think that, you might well consider suicide. I thought, “I don’t really want to be in this life. But I’ll give it one more chance.”

I’d heard about a Zen monastery which is in England.

The Ceremony Hall of Throssel Hole Buddhist Abbey, England. For nearly a year I spent most of my time here.

It’s run by 25 English monks, both men and women 50/50. They run it in the Japanese Zen Buddhist tradition. All we did all day, apart from gardening and cooking, was hours and hours of meditation. When you meditate, what you do is you turn down the volume of everything that’s going on inside you, as well as everything that’s going on outside. You don’t engage with media, you don’t engage with your usual opinionating and your thoughts, worries, concerns. It’s all happening, but you dive underneath that as if into an ocean. When you dive into an ocean, as people who’ve tried that [will know], everything outside becomes quiet and you go into a totally different world.

So I did that; and when I did that, what I came across was absolute abject terror. There was a layer of emotion that was utter fear. Not for any particular reason; it was like a primal fear that we’re born with already. If you listen to a baby crying [as if] in terror, there’s not necessarily any particular reason; it’s just there, it’s an instinct. I realised that what I’d been channeling in my usual surface irritability, that I’d been carrying in what I thought was my personality, was that fear that was coming up.

But I had to persevere, because there wasn’t really any way out. There was suicide, or find a way that I could live with the way that the world was and the way that I was. So I kept going, and about 7 or 8 months into meditation, I came across something utterly unexpected that I [hadn’t even known] existed. The only way that I can describe it, is love.

It came to me in the most unexpected way. I was gardening with a nun. She handed me a tiny little plant, about five millimetres. It had two little leaves, standing. It was light green, I remember it so well – and it was beaming. I’m not even exaggerating about that; it looked like light was emanating from it. This was only because I’d been turning down the volume on everything else, that I noticed this tiny little thing. It said, “I am extremely precious. I am life itself. And it’s your responsibility to take care of me.”

Normally I hate gardening; I grew up in a city and didn’t care about stuff like that. But I felt I had no choice but to honour it. So love exists in things, plants and nature; not just in people, and not just in romance. There’s something that Buddhists call ‘Indra’s Net’ that connects all of us, and all things. It means that everything that we do affects other people – even the tiniest little thing.

Once I took care of an elderly friend at the monastery. Her feet were very painful, so I was putting band-aids on them. I found myself in this posture of supplication. I was kneeling, and I realised that that is what love is: taking care of other people’s tiniest needs, if you can, if they need you. And always looking out for that.

There was another nun, who said “How are you?” I’d never been asked “how are you” in exactly the way that she did. The difference was that she really meant it. She waited for my answer, and she really cared what my answer was. She wasn’t saying it just to get something from me. I’d spent so many years in London that I wasn’t used to somebody actually caring about such little things.

So the nature of love with Indra’s Net, that network, is that it doesn’t come from us. It comes through us. We can’t control it, necessarily. It comes through us, both emanating from us, and something that we can receive. Receiving and giving is the exact same action. In helping my elderly friend, I was also receiving something.

If you look for the evidence, you’ll find it. My father wrote a letter to me at the monastery. He did his usual thing which was argue with me on a philosophical point. It always felt like a punch to the stomach; it felt like “Dad, you’re not acknowledging my reality” and it made me incredibly angry. I grabbed the letter, scrunched it up and unfolded it, scrunched it up and unfolded it, then took it to a Zen master and said “I’m so angry with my father, what can I do with this anger?”

I thought he was going to tell me to go and meditate or something. But he said “well think about, why did your father really send you that letter?” I realised, well, it was to connect with me. Why would he do that? Oh – he loves me. In less than a minute, I’d turned around this aggressive emotion into realisation of connection.

I was able to do that afterwards as well, when I went back to London, in very aggressive confrontations with complete strangers. It turns around. A lot of people obviously are quite desperate in London, and often they’d come up to my face. Usually I’d be really defensive and angry, and I’d try to push them away or something. But when I let them come up close and really try to find out what it was that they wanted, that was all they wanted. They just wanted to be heard. They didn’t actually want to hurt me. I think far too often, we’re very defensive and we imagine that people want to hurt us when they don’t.

You can also find evidence in the tiniest things like a little butterfly landing on your shoulder to show you that you’re not alone. Or there’s a social forum called ‘askreddit’, where seven million people write questions to each other – just because they’re interested in each other. That’s the only reason.

You can also find evidence in the tiniest things like a little butterfly landing on your shoulder to show you that you’re not alone. Or there’s a social forum called ‘askreddit’, where seven million people write questions to each other – just because they’re interested in each other. That’s the only reason.

I went back to London after about a year in the monastery, and it felt like there was this gigantic hand following me everywhere, protecting me. I don’t believe in such things; I’m just telling you how it felt. I like to test things, so I’d go from city to city and country to country to see if it’s still there. And it was. That nature of the net that I was talking about was protective.

Unfortunately though love doesn’t fix everything, as everybody here will know. There was still pain in the world, and there’s obviously still conflict and war, both individually and politically. Life is imperfect. As Leonard Cohen says, “there’s a crack in everything; that’s how the light gets in”. But these atrocities that so many people – probably all of us – are capable of, they’re actually just a twist in the fabric of love. It’s a misunderstanding by people who’ve only gone as far as that feeling of terror, and don’t realise that there’s something underneath it, that’s much greater than that.

For those of us who do know, we can choose to do that and act from the place of love rather than the place of terror. We can choose to judge things in terms of how different we are; or we can choose to judge things in terms of what we have in common. It makes all the difference.

The other thing that makes all the difference is to tell your truth to somebody who really knows how to listen. I’m training to be a counsellor, and as a trainee counsellor you have to go to a counsellor as well. I’ve learned to tell her about the things that I find the most shameful in myself. Things that other people have done to me, that I’ve been carrying all this time; things that I’ve been wanting to do to other people that I thought were awful. I had such guilt. I’m only telling you this because I know that every single person has that darkness in themselves as well. And that’s ok. It’s normal. And when you tell somebody, the act of telling somebody is almost like an alchemy. It transforms the feeling to something that you realise is actually ok. But I can say this, and it sounds like a textbook. It’s not until you actually do it, that it works. You should try it.

So after all of that – coming back from the monastery and spending several years back in London – I met my “true love” in my late 30s. The way that true love is often defined is “two souls are as one”, and that’s really how it felt. But it’s completely unpredictable. We had totally different lifestyles, completely different backgrounds, and I certainly didn’t expect to meet him in my 30s. I thought I was going to meet him when I was in my teens and have lots of kids. But things don’t work out the way you think they will, and the key to true love is in the word “true”. It was when I was honest with myself, let go of an agenda and stopped trying to make things happen, that love could actually happen. Otherwise, I was just pushing it away.

There are also many more souls in the world than just two. If you try to choose, “I’m going to like this person and not all of those other people. I’m not going to be loving towards that tribe, that community, that country or that political group”, then you’re actually shutting your heart off. Your heart only has “on” or “off”; you can’t choose to only love some people and not others. So if you decide to be in a loving relationship, you have to also be open to everybody else and vice versa. [I don’t mean] in an open sexual relationship, I’m talking about another kind of love!

Buddhists talk a lot about the “false self”. I think of the individual self as a crusty eggshell – that’s how it feels to me! Which keeps me away from other people. It isolates me. Whereas the fact is that we’re actually much more like blobs in a lava lamp. Waxy globules that are going along in a stream of lava-type liquid. If you think about a lava lamp, these blobs are always forming and unforming, and they change as they go along. They don’t have any preferences about it. They don’t point at each other and say “that one’s different”, or “I’d rather be like that”, or “I’d actually rather be over there”. They just go along with that flow, and that’s how human beings actually are. We have much less choice than we think. Of course there’s still wisdom, and there’s still good choices; but if we went along with the way things are, things would be much easier for us.

If you also think about the lava lamp in terms of these blobs forming and unforming, I don’t know how many people have experienced grief and loss here, but a lot of people will have the feeling that when somebody dies, it’s not over. That’s not the end. The only real thing there is is change, not necessarily living and dying as we think of it. It’s much more fluid than that.

Love isn’t some kind of magical thinking. It’s grace. And you honour it by letting go of the opinions that separate us; by honouring gentleness, both in yourself, and particularly in people you don’t like! That’s the greatest challenge. And also by telling your truth.

I’d like to end with a poem by 13th century poet Rumi. It’s quite a well-known poem, but it bears repeating:

Advice to a 20-year-old self

Yesterday I was asked by a young Buddhist, “what advice would you give to your 20-year-old self, when you were just starting on the path?” I answered,

Zen doesn’t mean that nothing matters. Money matters, work matters, every little interaction matters. Throw yourself into work – I mean, don’t get a heart attack over it, but you’d probably enjoy being an apprentice in TV – try it. It sounds superficial but it won’t be forever, and you’ll learn the skills you need such as working with fun teams of people, selling your ideas, and taking care of yourself materially. Don’t judge things and people so much – what’s the use? One day you will find that you were only judging yourself. The world really looks like the way you are inside.

That shit about never taking “no” for an answer? That’s only true when you’re on the right path. Sometimes it’s actually an indication that you’re on the wrong one.

There isn’t always a right answer. Sometimes you’ll just have to muddle through, so you might as well enjoy the scenery while you’re there.

Don’t go to university just because everybody else is – wait until you really want to, or until you’ve found a subject you love. You’re passionate about literature, right? That’s ok – you can study that. This is going to sound horribly elitist, but once you feel that you’ve got some measure of your shit together, try Oxbridge and the Ivy League, because you’ll regret if you don’t even try it. You’ll be meeting some really fun people from Yale, for instance. It doesn’t matter if the courses seem narrow-minded or aren’t vocational enough – you can make the time yours and do a conversion post-grad afterwards. Do more research before making such an important decision. You don’t want to be going to university forever. By research I mean keep looking until you find something that sounds really exciting to you. What would you do if you weren’t worried about the future? Don’t listen to dad – he loves you, but he has his own unintended agenda and he doesn’t know everything. The important thing with something like a degree is that you find something that you can go deeply into and enjoy. Then you will do well. Otherwise you will be acting against your own heart, and that won’t go far. Trust me. Trust your own intuition.

Travel is not more important than work. I’m not saying don’t travel, but also don’t try to walk in your parents’ footsteps – you are not them, and the world has changed. Make a base – not necessarily geographically, although that can help. Concentrate on making a living, then from there, you can find ways to travel. Doing it the other way round won’t work for you. Try not to chop and change so much. A little boredom won’t kill you. I’ve got some radical news – it doesn’t matter whether you become Secretary General of the UN, or a plumber. Choose something you enjoy doing, in the sense that you can throw yourself into it completely, but be open-minded about what that might be – especially at this stage. What matters is that it is your job, that you take pride in it and that you do your best. The thing is that no matter what you do, you will touch people’s lives. Don’t underestimate the value of that.

When you have ideas, don’t dismiss them or hide them because you’re afraid. Take them as seriously as you would take anyone’s ideas. Be proud of them and bring them forward. You are talented. Use it to serve.

Don’t go out with people just because you feel lonely. When you sleep with someone, they will forever be a part of you, in a way. Choose wisely and learn self-discipline. But don’t get too uptight or earnest! Have fun and let your hair down, too. Yes I know this advice is contradictory – that’s how things are. That’s why it’s hard. But it’s worth it, I promise, and you can do it. Persevere and do your best. Then rest in the knowledge that your best is enough.

Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. When you make mistakes, don’t cover them up – own up, and then move on. Please be humble – but don’t suffer low self-esteem. At your age, simply aim to be cheerful and to learn. Find mentors at work and absorb everything you can from them. Most people are basically kind; there is nothing to be afraid of. If you approach enough people honestly and humbly, some will agree to take you in as a trainee. This is an amazing and limited opportunity – treasure it and give it everything. Don’t worry about your doubts or your future. It will work itself out so that you don’t have to.

Make criticism your friend. It will often be clumsily given, but in your own mind you can make it constructive. People will give you feedback that you can use to become a better person. Whether you’re given criticism or a compliment, say “thank you”. There will be abusers too, though. That’s a whole different chapter, but you’ll save yourself a lot of trouble if you simply ignore them. They don’t deserve your attention.

Be kind and generous even if the world is falling apart around you, but don’t bend over backwards to make people like you. Some people will like you, some won’t. That’s the way things will always be. So the sooner you learn to march to the beat of your own drum, the better. Do the thing you think is right, and then if the landscape changes up ahead, it’s ok to adjust. Don’t judge things in black-and-white.

Treasure your body. It seems invincible, but you only have one, and one day it will age. You will be grateful then that you care for it now. I don’t mean weird spa treatments or that you have to run a marathon – you know what I mean. I know you are angry, but don’t take it out on yourself. Don’t hate where you come from; be proud. There is no one quite like you. The purpose and great challenge of our lives is to be ourselves completely – but you can’t second-guess what that is. You have to nurture yourself, and let it unfold gently. That process doesn’t end until you’re dead. That’ll hopefully be a long time from now, so you’ll need to develop some patience and steadfastness.

The world is complicated. There are people directing charities who are self-centered a-holes, and there are bankers who are kind and selfless. If you’re wondering why I took bankers as an example, it’s because in future people are going to really hate them. Human nature typically needs someone to blame. Keep seeing through it.

There is an honourable British tradition known as “taking the piss”. Learn it and use it liberally, particularly take the piss out of yourself.

As you’ll already be aware, some people will try to take advantage of you. The fact that you’re a woman can sometimes be hard. Remember that such people are the minority. It’s true that almost everyone has an agenda – but that agenda is simply that everyone wants to be loved. It’s just that it expresses itself in twisted ways sometimes. There will also be people – even friends inadvertently do this sometimes – who try to put you down, sometimes in the smallest most insidious ways. Never ever believe such stupidity. God knows you’re not perfect, but you are also brilliant and full of heart and potential. That stuff that mom used to say about how they’re only jealous, and you never believed her? It’s time to start believing her. You’ve got a great instinctive defense system – trust it. Tell people where to go, when they deserve it. Don’t let anyone or anything get to you. Don’t dwell on the upset that arises, it will only hurt you.

In a heartbeat friends can become enemies and vice versa. Despite appearances, consider everyone a friend at heart. It’s a bit of an art to do this without being a doormat. You’ll figure it out. Don’t be afraid to be close to people. Whatever arises – and I mean anything at all – you can learn to handle it.

Yes there is “true love”. It will be almost everything you hoped it would, and more. You will know beyond doubt when it happens. But you can’t make it happen, it won’t always look like you imagine it will, and it won’t miraculously make everything ok. So simply have faith; don’t waste your time going looking for it. You need to get on with your life and enjoy whatever you have now. Sometimes it will feel like you have nothing. But that won’t be true. Look carefully and find your passion again, even then. Especially then. I know Zen seems to say that passion is not the way to go, but if it’s about passion for life and you have an honest heart, it is.

Don’t be angry at life for always throwing you a new challenge. You like to think that if life stood still, we could all be happy and safe forever. You imagine that there would be no loss or pain. But if life stood still, there could be no change. Change is movement, and movement is life itself. Do you see? Without constant change and learning, we’d be dead. So embrace each challenge. I’m not saying “embrace it” because it’s the nice thing to do; I’m saying it because ultimately you have no choice, and because it’s the path of least pain.

You can enjoy fashion without being vain, and stuff without being greedy. So long as you keep your priorities straight, do it for fun, and remain willing to let go, such things help keep people like you grounded and happy. You weren’t meant to be a monk, so stop trying to act like one. Art, theatre, music and dance aren’t superficial – they’re fun and they’re important to you. There’s a film in which angels can’t see colour, and yearn to experience the passion that only the ups-and-downs of human life can give. You can tread where angels can’t. Savour it and experience it fully. Don’t stop going on your wild adventures. There are lots of worthwhile things to discover.

At the same time, don’t neglect the dishes. Try to get enough sleep most nights. Don’t make a habit of drinking too much coffee. Smile every day. Wear sunscreen (yes I’m serious. You’ve no idea.) Keep your promises, even if others don’t. Enjoy the little things: they add up. Moderation is your friend. It’s underrated. You will be very surprised at how deeply, earth-shatteringly not-boring moderation can truly be.

Your heart will break, more than once. I’m really sorry. I wish that weren’t so. If it’s any consolation, vets have a saying that if you leave all of a cat’s bones in the same room, when you turn your back the bones will uncannily find their own way back together and re-assemble themselves in perfect order. Hearts are like that too. I know, it feels like the world ends – but in the end, you will be ok. Other and better chances really will come to you when the time is right. Remember what I said about true love? Nothing that is real, can be lost. Trust, breathe, walk tall, and keep going. If you want to sometimes curl up and sob your heart out, that’s ok too. Walk through all the clouds; but don’t wallow.

Sometimes you will wonder if there is more to life. The answer is yes, a million times yes. When you feel like it, find a Zen monastery that you can learn from. Enlightened people exist all over the world, right now. It’s not mythical, a thing from the past, or only in Japan. It’s possible for everyone, and it doesn’t conflict with ambition or with ordinary life. Actually it’s a part of ordinary life – of your life.

Change your life for no one. Zen masters have important stuff to teach, but they don’t know everything about you personally. They would say as I will: follow your heart, continue to sit still within yourself, and know that you are loved – especially when it looks like you are all alone.

_____________

A short version of this post was published in The Huffington Post.

Did you hear my latest interview on BBC Radio London? Mixing Faiths – in interview with Jumoke Fashola

.How to enter a Zen monastery

Hi, I’m an 18-year-old recent high school graduate from France. I remember your article about staying in a Zen temple for a year. I am looking to do something similar. Could you tell me how you set that up, what you had to know beforehand, and that sort of thing? Thanks a lot, Ductile

Hi Ductile, That sounds exciting 🙂 I’ve had similar questions from different people who are interested in longer stays, so I’ll give you the long answer, and hopefully it’ll answer them too.

Getting started

Once I realised that I wanted to commit completely to studying Zen, it felt urgent. I rang up the first good monastery I heard of and said “I want to go there immediately!” The monk on the phone sounded bemused and said calmly, “well why don’t you start by attending an introductory weekend next month, then we’ll see?”

I was annoyed that he wasn’t taking me more seriously. There I was, ready to give my whole life to the Dharma, and he was suggesting a pesky beginners’ weekend? My ambition, I felt, carried more gravity than that. So why was I not being welcomed with open arms?

As the monk knew and I eventually found out, the answer is simple: you’ve got to start somewhere, and a weekend is a good start. The equivalent of my fantasy would be if someone with no experience decides they want to work in TV, so they ring up the BBC switchboard and expect to be given a job.

I’m not saying that this is what you think, and it doesn’t sound like you want to be ordained as a monk. It can be helpful to remember all the same, that even from a practical point of view monasticism is one of the most serious vocations there is.

The entire monastic community is signing up to work side-by-side with you day and night, seven days a week. In many temples there’s no privacy at all, and you eat and sleep in the same room together. In a relatively closed and sensitive community, every personality has a magnified effect on all the others and vice-versa. It’s a pressure cooker. If one person gives up, messes up or leaves – which happens as often as it does in any other job – it feels like a serious blow to everyone who is left behind.

So it’s safe to say that they’re going to want to get to know you before signing you up to a longer stay. Along I went to the introductory weekend, at a temple that someone had recommended.

The first question

The question to ask yourself after the introduction is not “do they like me”, but do you like them? Not in a sentimental way, but rather, do you trust them to be reliable teachers? Do they seem to know what they are talking about? Does the kindness and compassion they preach show in their day-to-day actions? Are they genuinely humble and yet confident? How do they handle conflict or disagreements? Do you feel respected and at ease? In some places (sects in particular), the question to ask yourself is are they manipulative or trying too hard to impress you?

Trust your gut feeling on whether it’s the right place for you. This can be tricky because most of us have mixed feelings when we start spiritual training. I was suffering and confused when I started out, and projected my pain everywhere I went. As a result, the main impression I got in my introductory weekend was that everyone was irritating!

However, despite this I could tell that the teachers knew what they were talking about. All my questions were answered with care. If a teacher didn’t know the answer, they were happy to admit it. Both teachers and long-term students seemed content and relaxed, and yet they weren’t going around boasting that I needed them or that theirs was the best school among all schools. There was no pressure on me to join, and there certainly wasn’t any pressure to pay donations.

A common complaint among beginners is that they don’t get as much access to the teachers as they would like. Again, this is something that builds up with time and patience. As in any school, beginners are often assigned junior teachers, and senior students then see more of the senior teachers. You wouldn’t expect to immediately get regular meetings with the abbot, although in smaller priories where there are only two staff, that’s more likely.

Sustained practice

After the introductory weekend I signed up to a week-long retreat, which went equally well, although it was hard. I was learning so much and felt like I couldn’t get enough, so I started to attend as many week-long retreats as I could. Gradually over several years, I got to know the monks and they got to know me. It was a very slow process, because the monastery isn’t a social club exactly, and most of the time we don’t say anything at all.

After about five week-long retreats, I still felt that I would benefit from staying longer-term. So I spoke with the Guest Master and then the Abbot to explain why I felt that way. Together with other senior monks they then considered my progress so far, and whether they agreed that I would benefit. It wasn’t a case of whether I was “accepted” or not. It felt more like we were all considering together whether a longer stay was the right path for me at that time, and if so, if that was the right place for me to do it.

All I could do was be honest about how things looked to me, and then be open to the views of the hosts. It didn’t help to be attached in my mind to the idea that I had to stay “or else my life will be directionless”. Be confident that there are always other paths. The way to find the right one is to accept that you don’t know the whole picture, and to be willing for any of those paths to be the ‘right’ one.

To get back to how the admin worked: I asked to stay for nine months simply because my gut feeling was that that’s how long I needed to stay to learn the practice. The abbot responded, “Maybe. Start with three months, then we’ll see.” Every week, I reported back to let him know how things were going. My reasons for residency were reviewed a couple of times during the stay, and eventually it felt like the right time to leave.

Other temples have long-term residential structures worked out and you can apply formally, but the spirit of the process is similar. These days almost all of this info is easily available on temple websites. At the very least, there’ll be a phone number you can ring and ask them about how to get started. The most comprehensive online directory is Buddhanet, or you can simply google e.g. “Zen” and your area. If you ask enough people for their advice, you’ll soon figure out which places have the most solid reputation.

Do you need to know anything beforehand?

The less the better, I can imagine some teachers saying 🙂 They taught us everything we needed to know at the introductory weekend, and on the website they said what things we might need. (Working clothes, toiletries. Obviously.) What I’d also learned to bring is a rather pedestrian list:

- A blindfold, to help me sleep on bright summer nights

- Earplugs. We shared a large room and people snore.

- Insect repellent in summertime

- Smart but comfortable clothes. Some people wander around in tracksuits, but I feel more respectful in trousers and a shirt.

- Wet tissues to clean up fast, because often there’s little time between a work period and a talk.

- Small packs of tissues to salvage my hayfever with, and pockets in all my clothes to keep them in.

- Shoes that are quick to slip in and out of, since we take our shoes off when popping in and out of the cloister. You’ll also need a pair to get muddy in outdoors.

- For long stays: small things you might want to gift to new friends, e.g. small packs of chocolate or little souvenirs.

- My friend Jason is very fluffy coming back from retreat just now, and would like to add that men tend to forget: a razor, nail scissors, dental floss and tweezers.

What I realised I didn’t need was

- Books – the emphasis was on practice, not reading, and we were encouraged to take a break from what we normally do (for me, that’s reading.) There are books there, as well.

- Computers and a phone. It’s liberating to take a break from these things we enslave ourselves to every day. The temple was out of range anyway, and there’s a guest phone when you need one.

- A stinky deodorant. It’s really embarrassing at close quarters. Stinky sweat is embarrassing too, of course. See “wet tissue” entry above and bring toiletries that don’t smell.

That’s enough about deodorants. What about the intellectual stuff?

From a point of view of zazen practice, I’d suggest that the less you know the better. Some of my fellow trainees had taught Buddhism for 25 years, but it was all intellect-based so they felt that they had to start from scratch. What the monastery does is point you back to your sitting cushion, and you don’t need anything to do that. They even supply the cushions (or chairs, for the many trainees who can’t sit on the floor).

One of the things that surprised me the most was the other trainees. In my solipsistic mind, I’d imagined that they’d all be like me – i.e. in their 30s, single-minded in a sort of masculine way, flown in from all over Europe, and dressed in black. But there were all sorts. Most were actually easy-going retired men and women from the local area. Don’t be disappointed if it isn’t what you expect 🙂

Another piece of advice I’d give myself in retrospect is, don’t take everything that all teachers say to heart. Not even masters are necessarily clued up about how emotional psychology works. Insight into the Dharma is not the same as worldly awareness, and understanding compassion doesn’t guarantee that they’re going to put your interests first. I gratefully soaked up every word of every formal Dharma talk; but there were things said in between to trainees personally, that were not always on the mark. Ultimately the only person who can know you and stand up for you, is you. Concentrate on your own training, while being kind to those you find yourself working with. Keep a non-judgmental and humble beginner’s attitude, but at the same time, trust yourself.

I hope this answers your questions. If not, please ask more.

.