Make A Wish Like A Zen Monk

Last New Year’s Eve, I was moved by a talk that a Zen monk gave about how to make a wish. It struck me as a skill that everyone could benefit from, and not just at New Year’s, so he kindly let me publish a short version of it here. (You can also listen to the full talk here.)

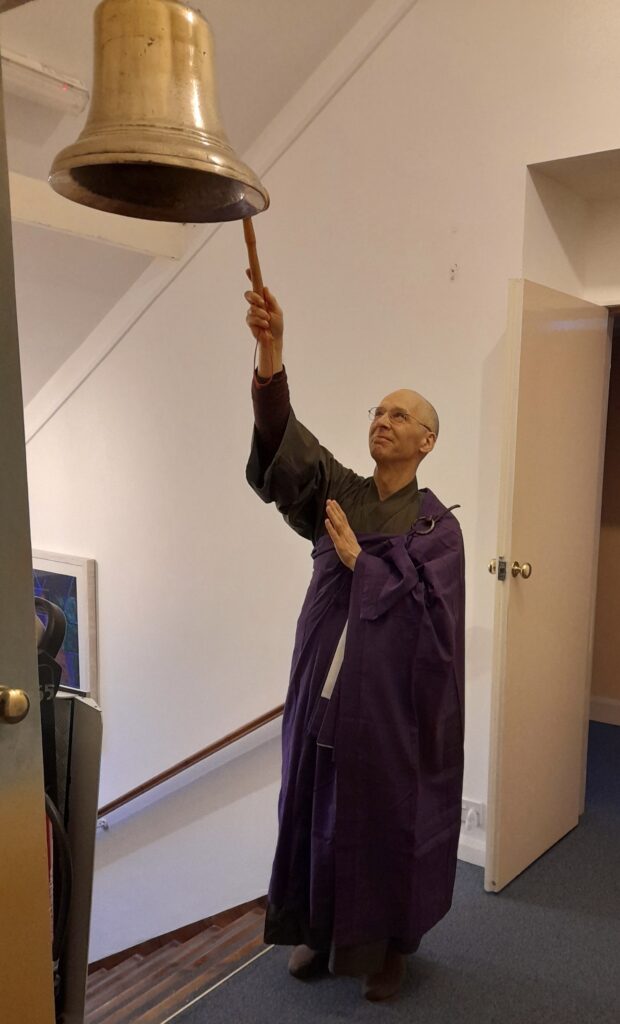

“At the abbey we celebrate the New Year by gathering at the altar, and revolving the Scripture of Great Wisdom (also known as the Heart Sutra). The celebrant opens the scripture like a concertina and revolves it around, to symbolise what we think of as the living and moving qualities of the truth. At the end of the ceremony, each participant in turn rings the big monastery bell. In that moment they silently make a wish — or a vow — for the coming year.

You could do your own version of this at home: maybe do some meditation in the evening, offer incense or strike a small bell if you have one, and make your own wish or vow.

What I’d like to focus on in this talk is the attitude of mind that we have when doing that. New Year’s resolutions can be tricky: while it’s natural to have an aspiration to improve yourself or your life, the goal-setting in itself can become just another distraction or avoidance. In her recent book ‘A Mindfulness Guide For Survival’, well-known comedian Ruby Wax writes well about our reactions to covid, and of typical forms of avoidance:

“We were suddenly forced to confront the harsh truths of difficult emotions, uncertainty, loneliness, change, dissatisfaction and death… […] Of course, deep down, we know everything changes and everything is uncertain. We’re alone, we die, blah blah blah. But who wants to go there, when there’s so much on Netflix to watch? […] We’ve been too busy to notice disturbing realities because we were all on a tight schedule of ‘must do’ things—most of which were things that didn’t ever need to be done.”

We can be trapped by so-called time-saving devices like the smartphone but are at its beck and call, waiting for it to ping so that we can ping back. I have a smartphone and occasionally measure how many steps I take in a week to keep myself fit, so I can appreciate how anything like that can become a bit addictive.

What all this is pointing out, for me, is that we need to clarify the wish we make in a way that isn’t just another form of measurement or another ‘must do’ thing. We need to get underneath the whole concept of ‘things we must do’. What are the real ‘must do’ things? If we were going to ask ourselves just a single question to clarify what our wish is, it would be: What is the most important thing?

Self-help techniques, mindfulness techniques, and ways of measuring progress, can be very helpful; they can give stability when you’re dealing with for example depression, or finding ways of coping with daily life. I’m not knocking those.

Sometimes, however, they can also encourage an unhelpful kind of thinking, where we see ourselves as objects—as if we’re watching ourselves in a movie, to see how well we’re performing. The next thing we know, we’re measuring our progress in terms of how much meditation we do. Then we install an app to measure meditation—and our wish has become just another ‘must do’ thing.

A real wish is much deeper than that. Don’t let yourself avoid the question, What is this self? What is this being, that wants to achieve?

If you achieved all your measurable goals, would you be happy? Or would there still be a sense of lack, if you’re not careful? If you achieve 6,000 steps a day for example, maybe you’ll be fitter. But the ‘being’ that’s on a fitness app in terms of heart rate, number of steps, and hours of sleep, must not be confused with what you really are.

Not everything can be measured in terms of success and failure, because no matter what we achieve there’d still be a ‘me’ that seems to be the centre of existence; that seeks to control the world in order to find the most comfortable place. It’s an instinct. We’re so used to controlling things; to thinking about what we want to achieve and how to achieve it. We want to know what is happening, so that we can control the results. This works well—to a point. As soon as for example our health fails though, it’s clear that we’re not in control. Some things cannot be known in the way that we’d like.

We can learn to respect that; to accept and acknowledge that there’s a horizon over which we cannot see. That allows us to remain in awe of life and death, and to have a more realistic sense of our limits. It’s ok for some things to remain as question marks, without our seeking reassurance.

To bring this back to making a wish: maybe just for the moment we need to cease from measuring completely, and just trust the intention and its sincerity. What is the most important thing?

Zen Master Dōgen wrote that if you “simply let go of body and mind and let body and mind fall away naturally”, you will “effortlessly gain freedom from suffering”. I sometimes wonder about the ‘effortlessly’, and suspect that it actually takes a particular kind of effort just to remind ourselves not to let our vanity and ego get in the way. There’s a difference between a practice based on protecting and enhancing the ‘me’, and a practice that sees through the illusion that we are the centre of existence.

In our practice, there’s bowing. The founder of the monastery was taught that when bowing stops, Buddhism stops. Interestingly, the more senior you become in the monastery, the more bows you have to do! Three before meditation, and six before and after morning service. It’s all to remind you that while you might be ‘in the centre’ at the moment, there’s more to it. It’s an acknowledgment that “I don’t know everything, and never will. I don’t even know what will happen today, but I will do my best. However important I may feel myself to be, there is always much more…”

This doesn’t mean that there’s a higher being, necessarily; it’s simply a sense that our relationship with existence is deeper than we can fathom. My body, life, mind, and time are not really mine: they are ‘owned’ by the world. We have some control, but what could any of us do without the support of everything around us? Our lives are constantly connected to that of others, and to existence itself.

Bearing these things in mind, the personal wish or vow that we may want to make has to come from within. Leaving aside what we are told that we must do or must have, just by looking for it we are doing something positive. What is it within ourselves that we can trust?

We can sit through many things. Just as the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree before his enlightenment, we can allow all the pulls and pushes, the pressures, all the things we feel we must do, to settle so that we can clarify out what is truly important. Help is available, whatever you may call it: intuition, Buddha nature, a still small voice.

Don’t worry if it seems trivial. It could be as simple as being kinder to someone you know. Just doing one thing with a sincere mind is always enough. We don’t need to vow to save the world. The moment of respect, or an act of offering—even bowing once, or making a sincere wish—can transform the mind, and even embrace the whole universe.

The physical act helps. It’s in the doing that our connection is realised, and it works because of that connection. Our efforts may not save all refugees or stop global warming; but there is something inherently good in making the offering, that warms the heart and connects all beings.

Clarifying your wish is ongoing. It’s fine for it to remain undefined, as long as you keep reaching. The searching and the goal are not separate; the asking and the answer are not separate. They come together. So strike a bell, or do some bows, or light a stick of incense. Make your wish, and trust your heart in doing so.”

Edited from a talk by Rev. Berwyn Watson.

(Find out more about Throssel Hole Buddhist Abbey on Facebook or Youtube.)