Does Buddhism Really Work? Buddhism and Psychotherapy

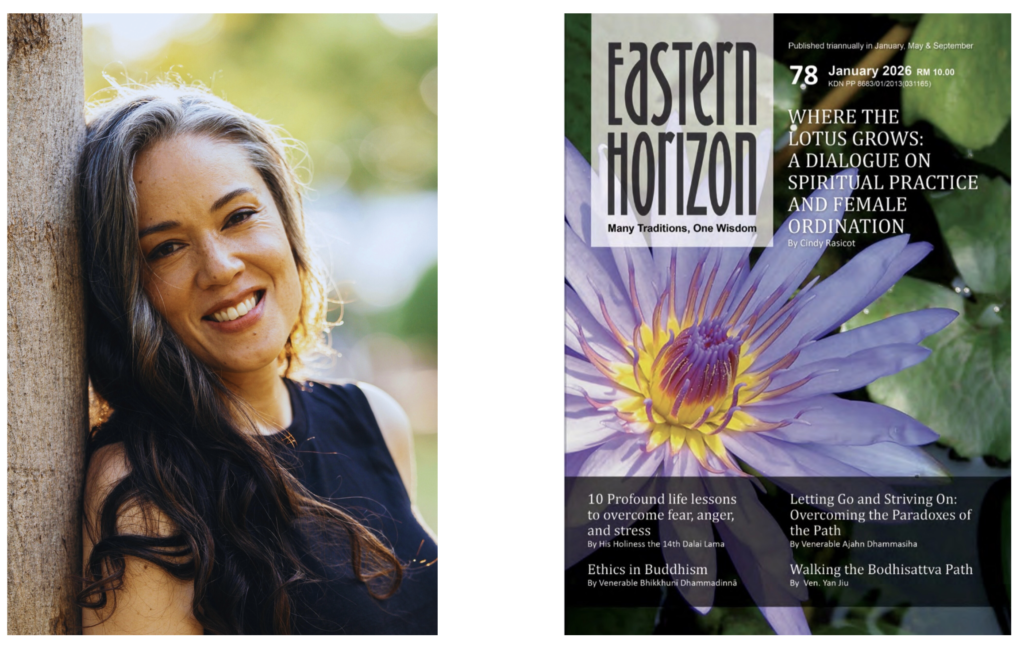

‘Can Zen Make Us Happier? Buddhist Wisdom for Modern Lives and Busy Minds‘ is an interview with Mia Livingston and Benny Liow, Editor of the Young Buddhist Association of Malaysia’s magazine Eastern Horizon (pp. 51-55, January 2026)

Mia Livingston is a doctoral candidate researching somatic psychotherapy and autoethnography at the University of Edinburgh. Featured in TEDx, the Guardian, BBC Radio and as editor to the Buddhist Society in the UK, she has been studying and writing about Zen Buddhism since 2004. Benny Liow was able to interview Mia about her interest in Buddhism, especially Zen, and the relevance of Zen Buddhist teachings for the well-being and happiness of today’s much stressed society.

______

Benny: Can you tell us about how you first became interested in Zen? Was there a particular moment or experience that drew you to the practice?

Mia: In retrospect I was drawn to Zen before I knew what it was. Even as a small child, I felt consumed with a search for answers to suffering and to the meaning of life. But nowhere I looked and no one I asked seemed to know the answers, until finally aged nineteen I came across Philip Kapleau’s classic work The Three Pillars of Zen.

I devoured it, amazed to learn that such an ancient wisdom practice was still alive somewhere in the world today. This was before the internet, so as far as I knew, the only places you could study Zen were monasteries in Japan. I resolved to go there and study as soon as I could. Until then, following the detailed instructions in the book, I tried to sit zazen at home on my own—bunching up some pillows and sitting cross-legged on a mattress for a few minutes at a time.

It was extremely hard of course. Without a teacher I got nowhere. Abiding quietly in my mind felt like entering a storm without a lifeline. I gave up until a few years later, when I had the opportunity to attend Vipassana sessions at university.

It was much easier to sit with others. But my intellectual mind was still much stronger than my ability to sit, so when university ended my practice did too.

Day-to-day life took over for some years until a woman I interviewed during my work warmly recommended S.N. Goenka’s ten-day Vipassana sits. That enabled me to go a little deeper, and yet I knew I was only scratching the surface. I still had so many questions that it seemed nobody could answer.

Finally aged thirty-three, I found Zen in practice. I was struggling in all aspects of life. My relationship, family situation, work and friendships all seemed to be going horribly wrong. There was nothing to hold on to; it felt like I had nothing to live for. With perfect timing, an acquaintance mentioned in passing a Zen retreat not too far away that he’d attended. I was amazed—that was the first that I’d heard of there being Zen retreats in the modern day and in my country. Maybe I wouldn’t have to travel to Japan after all?

I phoned them. They said that they were booked full, but recommended a monastery further north. The monastery said that they were fully booked too, but I must have sounded desperate because they kindly made an exception and let me come for the next introductory weekend.

Finally, I felt that I had found my place. About twenty-five monks were resident there, and many of them were able to answer my questions. I loved the way that they came across: calm and modest, but also light-hearted and compassionate. They had a library and several monks had doctorates, which meant that they taught Buddhism in a way that my overly critical intellectual mind too could engage with.

I returned as often as I could for a week’s sesshin (intensive retreat) at a time. I was a hard nut to crack. Despite all the zazen and studying, I continued to feel full of despair. Meanwhile my situation at home was deteriorating. There seemed to be only one thing for it: I asked if I could stay longer as a resident. These days there are many organized residential programs that you can easily apply to online. Back then and there, unless you wished to be a monk it was unheard of.

They were tentative and reviewed my stay every few months, but I ended up staying for a year. I actually felt from the start that that was the amount of time that I would need for my understanding to gain sufficient traction to be able to continue on my own.

Many have asked me why I didn’t “just” stay and apply to become a monk. They assumed that anyone who could, should and would apply to walk that path. My answer to that question is hard to explain. I wanted to want to. I loved the teachings and the monastic community; while it wasn’t easy, I felt happy and at home there; and no relationship, desire, or job was calling to me from “the world” (as life outside the monastery is often referred to). In one article I joked that “I feel more at home in a whisky bar than an abbey”, although the truth is that I feel equally at home in both. (That said, if I had to choose one, I’d choose the abbey!)

I was driven by an unformed and yet certain feeling of having a vocation “in the world”. As I mentioned before, I felt consumed from an early age with a search for answers to suffering and to the meaning of life. But it was more than that: I felt driven to apply those answers to whichever form that suffering was currently taking among people in general. And in order to do that, I had to be in the midst of it with people who were going through relationships, anxieties, politics and so on.

I felt grief about that choice—it seems common for us humans to feel grief about whichever paths that we don’t take. At the same time, there is gratitude for the richness and joys that come my way.

I ended up studying and qualifying as a psychotherapist. Currently I am a doctoral candidate studying experientially the influence of somatic psychotherapy and Zen Buddhist practice on the healing of complex trauma. I’m also a writer, and aim for my research to be published in book form eventually.

From your own experience, how has Zen practice influenced your sense of well-being or happiness? Are there particular aspects of Zen that have been especially helpful?

When I found myself not knowing what to say in sanzen (private interview), my first Zen teacher would ask me “what feels important right now?” or simply “what’s important?” My therapist asked the same thing, and I learned to always go back to that until it eventually became an inner “place” that I habitually “lived in”, a compass that I navigated by. The question led to what feels like a big, calm and quiet space in my gut, and it’s a perspective that undercuts anxiety and slows time down. (If there was a song for it, it would be Louis Armstrong’s “We have all the time in the world”.) This depth of being results in being less swayed by the caprices and pulls of our constantly changing world.

Contrary to what I thought would happen, slowing down has actually allowed for more activity rather than less. Life became bigger and could hold more. Despite being in my 50s I’m much more active, confident and positively motivated now than I was when young.

There’s also an impulse towards connection that clarified with practice. I used to jump into new friendships and jobs without thinking much about it. The impulse that arises from Zen practice skews more naturally towards service. I ask myself what I can add to a situation if anything. If I can’t add anything then I don’t engage. If I can, then it often happens instinctively. And it goes both ways: I only engage with new friends or work when the connection is nurturing. This may seem obvious, but from a psychotherapeutic perspective there are many unhealthy reasons why people engage. Friendships, work and relationships are healthier now.

As both a psychotherapist and a Zen practitioner, do you see similarities between Zen practice and psychotherapy when it comes to supporting mental health? Where do they align or diverge?

I think they both have the capacity to contribute to the alleviation of suffering, and personally I needed both. You could think of it as Zen forming the bones of practice and psychotherapy the flesh. While Zen eventually (and slowly) woke me up to the direction and purpose of my life, psychotherapy taught me how to walk that path. But there is no clear-cut line between the two; they overlap, and everyone’s needs and experiences vary.

One major difference is that while Zen training took place within a community, ultimately you can only do your own training, and you can only do that within yourself. Even though Zen Buddhists often sit side-by-side, it’s mostly silent and it can feel lonely. Psychotherapy on the other hand is social by nature, because you’re figuring things out together with a group or a person.

After years of sitting zazen and solitude in my life generally, I thought I was very good at being alone and at abiding by the precepts. But it turned out that I had just been repeating the same egotistically defensive narrative over and over again in my mind. I could act in accordance with the Zen community and my narrative might have refined a bit, but it was still there. Only psychotherapeutic inquiry with other people could and would break through that.

An insightful Zen teacher and a good psychotherapist see different things. Some trainees imagine that their Zen teacher sees everything; but even when a Zen teacher is a trained therapist, I don’t know if that’s true. It can be healthy to have multiple mentors, teachers, and sources of support.

Your research focuses on “personal narrative” — how do you see the role of storytelling or self-understanding in Zen practice, which often emphasizes letting go of the self?

Storytelling has likely existed for as long as humans have; it’s a way of sharing, connecting and healing. And in a very real sense, while we are connected, we are also separate individual human beings having separate individual human experiences. What is this strange life that we’re living, and what are we all learning from it? In my experience ignoring our differences is more harmful than acknowledging and maybe even celebrating them. Writing about the particulars of personal experience spreads understanding and empathy. It also taps into the universal, and can be a way of sharing Buddhist practice.

I work with autoethnography, which emphasizes understanding and writing about everything that both the “big” and “small” self is connected to, mutually influenced and sustained by. This includes relationships with humans and non-humans. It’s a kind of storytelling that seeks to clarify the role and place of the self as one of an infinite number of beings in an equal (if not always equitable) universe.

For sure there are forms of personal narrative which are unhelpful. You could do it for attention-seeking, or you might cast yourself perpetually in the role of a victim. Alternatively, through for example somatic psychotherapy, you could share deeply and honestly about painful experiences in a way which helps to connect us and process your karma for yourself and others. It would be a shame to miss out on the healing and connecting power of storytelling for fear of the former. After some practice you can trust yourself to feel the difference, and if you take refuge in the precepts, you can’t go far wrong.

Zen is often associated with monastic life. How do you see its relevance for laypeople — especially those balancing work, family, and modern responsibilities?

Many monastic friends have agreed with me that we do not see a significant difference on either a deeper or day-to-day level between monastic and lay life. Monks have numerous responsibilities that they balance too—monasticism can even be more hectic than lay life. Both monks and lay people take vows, practice zazen, study the Dharma, do their best to follow the precepts, do the dishes and laundry, cook, clean, work, exercise, relax, socialize, and care for our family or community.

So what then is the real difference between us? As I understand it, monastics are the formal lineage holders and teachers of the Dharma. It is their work, their vocation, and there are daily rules and rituals in place that support them to carry out those responsibilities.

As a lay person, on the other hand, I am not formally a Buddhist teacher. I’m Buddhist and I teach—but that’s not the same thing. I don’t take disciples or conduct ceremonies. I have taken the lay precepts and I strive for my work to be helpful and compassionate; but all my actions and choices are not held to anywhere near as close scrutiny as a monastic’s.

You could argue therefore that the teachings are more important to lay people than to monastics, because they are not built into our lives in the same way. Zen teachings have given me a solid sense of guidance and direction in all the areas that you mention. In other words, Zen couldn’t be more relevant to my lay life. In terms of the heart of the matter—compassion, freedom from suffering, and our commitment to do the best that we can—the relevance of and our need for Zen practice is the same.

Could you share a few ways you personally integrate Zen into daily life? Are there small practices or shifts in perspective that lay practitioners might find useful or accessible?

Moving your body gently can shift your mindset to a more open and nurturing one. I love doing kinhin (slow walking meditation) whenever I feel the need to slow down or get clarity. It’s no substitute for seated meditation; but it’s quick and easy to just get up from your work or chore for a minute, put one foot in front of the other, and notice every small part of the sole of the foot as it slowly, gradually comes to rest on the floor.

Another way that I integrate Zen into daily life is during challenging conversations, when possible. If I feel a conversation starting to turn into an argument or upset, I drop my attention down into my lower abdomen in the same way that I do in zazen, and ask myself questions from that place. Do I feel afraid? Worried? Protective? Why? Often it’s possible to begin to get to the bottom of something, which in turn can change and deepen the course of a conversation.

Have there been moments where Zen practice felt difficult or even conflicted with your emotional needs or relationships? How did you work through those tensions?

As a person with neurodivergence and a history of complex trauma, the harsh and collectivist training model traditionally used in Zen Buddhism was not always healthy for me. Any needs or sensitivities that differed from the norm might be judged by some well-meaning teachers to be self-indulgent, deluded, or “not training hard enough”. But there is room for gentleness and understanding without compromising rigor and veracity. It isn’t an easy balance to strike—but many teachers have done a great job of it, and the tradition is progressing in the direction of understanding trauma. Personally too, following autoimmune health issues I’ve had to learn to be much kinder to myself mentally and physically.

Related to that, I had to relearn assertiveness and healthy boundaries. Zen training can be confusing: students learn a spiritual practice of deep acceptance, but there will be people who take advantage of them because of that. They are taught to be like the old man in the parable of the lost horse where he remains equanimous regardless of gains, losses and others’ judgments. Righteous and constructive anger—and arguably even most forms of emotional expression—are not encouraged. I was praised as a trainee when I twisted my body and exhibited the traumatic “freeze” response. Following this logic to take an extreme example, what happens in cases of assault or unfair dismissal from work? I had to “un-freeze”, regain access to my full register of emotional expression, and learn to defend myself—even though in Zen understanding there is not ultimately a “self” to defend.

Has your understanding of “well-being” or “happiness” changed as your Zen practice deepened? If so, how would you describe that shift?

One thing that I wasn’t expecting is how sensitive, aware and fully engaged with my environment that I would feel after years of practice. For some reason I had interpreted “inner peace” to mean a sort of dissociation from the world; but the reality is the opposite of that.

I also thought that joy and the feeling of nurturing would come from some kind of holy “other” spiritual place. But it comes from that very grounded connection with your environment and all the things and people that you encounter in it.

_____

© Mia Livingston 2026. All rights reserved. Welcome to quote and link to this article, but do not edit or reproduce it in any form without permission.